2007年VOA标准英语-Human Rights Watch: West African Girls Work in(在线收听)

Dakar

15 June 2007

Across Africa, poverty and a tradition of putting children in the care of the extended family have led many parents to send their young children, especially daughters, to cities. There they often end up working in slave-like conditions. Now, a new Human Rights Watch report timed to coincide with the annual Day of the African Child has outlined the life faced by many of the young girls who leave their homes for work in the city. Naomi Schwarz has this report from our regional bureau in Dakar.

|

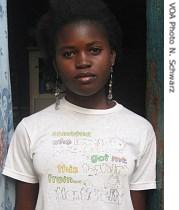

| Fatou Diouf |

It is six in the evening and she has just returned from work.

Work is very hard, but since she has nothing else she can do, she says she is used to it.

She comes from a small village several hours away from the capital of Senegal, Dakar, where she lives now.

Her family sent her to Dakar when she was 10 years old to work in the home of a family member, doing housework and taking care of children. She later left that family and took other jobs.

She says when she is alone, she thinks of her family and misses them. Diouf says she sends money back to her parents in the village. She never went to school.

In a Human Rights Watch report released Friday about girl domestic workers in Guinea, the author, Juliane Kippenberg, says there are a number of reasons parents send their children to work.

"There might be just really a situation of acute poverty or even crisis in a family, like death, illness, or divorce, that creates a difficult situation for the remaining parent," she noted.

She says a study by the United Nations International Labor Organization found that more than 70 percent of Guinean children under age 18 work, and more than 60 percent of those work in domestic labor.

Kippenberg says some children are sent to live with another family in the hopes that life in the city will provide the child with better options. Others are recruited by child traffickers, who promise good jobs in a faraway city.

But Kippenberg says in both situations, the promise of a better life almost never materializes.

"What happens is usually that these girls are not paid at all. Or if they are paid, they are paid a pittance," she said. "They work very hard, up to 18 hours a day and usually have no day of rest and certainly no holiday. This is sort of labor exploitation really. But I also found a lot of physical and sexual abuse against these girls."

Kippenberg says governments focus too strongly on stopping trafficking across borders.

"It is not sufficient to focus on the movement aspect, the transport, and the migration," she added. "Really it is very important to look at the exploitation that happens."

She says non-governmental organizations are filling the gap to try to get girls out of abusive situations, but they are not enough. She says she hopes to see governments across West Africa make stronger efforts to prosecute abuses, establish systems to monitor children's welfare, and keep all children in school.